FONGIT: The Swiss Valley Model

FONGIT is one of the largest tech incubators in Switzerland. I spoke with Managing Director, Antonio Gambardella, who is advocating for a new innovation model.

Meeting Antonio Gambardella is always a joyful experience, not only because he is Italian and communicates in a cheerful tone but also because he is one of the best observers of and contributors to the tech community in Switzerland. Having been both VC (General Partner of MyQube) and an investor with active roles in different companies, he knows the business-investment side and the entrepreneurial side. Since 2014, he has been the Managing Director of FONGIT, "the leading innovation incubator in Switzerland," which has more than 100 start-ups and projects in ICT, advanced engineering, and life sciences to its name. FONGIT has supported several successful ventures, including Anteis (sold to Merz Pharma in 2013), Selexis (sold to JSR Life Sciences in 2017), and Proton Technologies (global leader today in encrypted messaging service with more than 60 million users). Even more interesting, however, is how FONGIT departs from the purely hypercapitalist Silicon Valley model. In fact, many FONGIT companies have silently managed to grow and break even with a relatively limited injection of venture capital. That's something I asked Antonio to elaborate on.

Tribute to Silicon Valley

Our conversation started with Antonio's acknowledging Silicon Valley's significant contribution to society: "It has made possible the rapid development and introduction of new technologies. It has accelerated everything, and we all benefit from it."

According to Antonio, this model is prosperous thanks to its supportive community. "Silicon Valley is like a club. Everyone knows everyone else. They talk to each other frequently and support each other," he said. Founders know that they can have access to capital and excellent support at every stage of their project. On the investment side, VCs actively cover the entire value chain from zero to IPO. "If the investment stage is deemed too early for institutional funding, angels intervene, and sometimes general partners can even invest personally. Then VCs take over before later stage, and private equity funds come into play. Once a company has managed to partner with a Tier 1 fund, effortless fundraising is almost guaranteed until exit," Antonio said.

"For some companies that are capital intensive (e.g., deep tech) or with a high-risk profile (e.g., life science), there is no other choice," he said. These entrepreneurs have to approach VCs, raise a lot of money, and meet investor expectations. But this model has severe limitations and is not optimal for all projects. "One of my roles at FONGIT is to make sure that founders know the pros and cons of the model and are aware of the alternatives," Antonio told me.

The Unicorn Trap

To explain one of the limitations of the Silicon Valley model, Antonio refers to Jeffrey Funk, a technology consultant who wrote The Crisis of Venture Capital: Fixing America's Broken Start-Up System. This article describes how a new generation of start-ups backed by VCs is a financial disaster. Here is an extract of this must-read article:

The most significant problem for today’s start-ups is that there have been few if any new technologies to exploit. The internet, which was a breakthrough technology thirty years ago, has matured. As a result, many of today’s start-up unicorns are comparatively low-tech, even with the advent of the smartphone—perhaps the biggest technological breakthrough of the twenty-first century—fourteen years ago. […] This lack of revolutionary technology has made it hard for unicorns to create value at a scale necessary to be profitable. [...] University engineering and science programs are also failing us, because they are not creating the breakthrough technologies that America and its start-ups need.

Venture capital is no longer necessarily a synonym for building reliable and profitable companies in the digital sector. Instead, it's meant to shorten the time to market, quickly create moats, and trigger what Antonio calls the "Escape Velocity": the minimum distance and speed a company needs to outpace the competition and escape potential threats. "If the company can do that, it becomes a standard and can accelerate further. Spotify, which has defeated Deezer and now dominates the music industry, is a good example," Antonio said.

But if that scenario fails, companies can fall into the "Unicorn Trap." A VC-backed company is stuck between two realities: On the one hand, there is some pressure from investors who expect a sharp increase in valuation every year, and on the other hand, there is an economic reality that does not justify such an increase in value. "A gap is created between the market price (too high) and the actual value of the company," Antonio said.

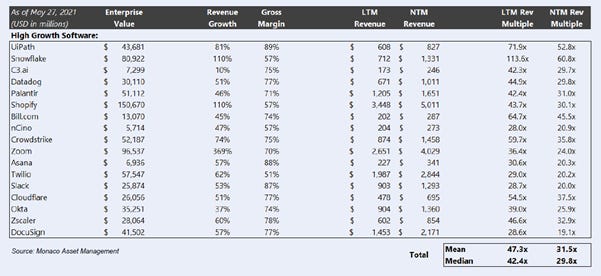

In the real world (a restaurant, a factory, or a company producing a good), revenue multiples rarely exceed 5x. In the SaaS world, for a company with recurring revenues, an EBITDA margin of 30%, and strong growth, the market would normally expect multiples of 20 to 30 times the revenue. But in the US, valuations can be 2 to 4 times higher, with a range of 50x to 100x sales (e.g., Snowflakes). Such assumptions can be unrealistic considering the size of the market and its growth rate.

As long as the company is still private and supported by the VC and Private Equity community, this price-value disparity can be hidden. In reality, however, "It's like a pyramid scheme built upon the subsequent phases of private financing rounds," said Antonio. And once the public markets are called on (for IPO exit), this phenomen may stop as traditional investors will not buy the deal. The risk for the company is that it remains private for a long time and then can neither raise additional funds nor exit, hence the trap.

Factors of change

"Society is changing. We are more aware that it takes time to build things and that it's okay to wait," Antonio said. He gave a personal example: "My 10-year-old daughter does not drive, and that's totally fine as she is not ready yet." Antonio sees the pace of time as a natural process: "Nature has its own pace of building things, and society should follow it." Similarly, it takes time to build long-term sustainable companies, and tech innovation is a long-haul endeavor.

The logic of Silicon Valley is different because it is designed to speed everything up. "Once you receive capital from a VC, your enemy is time," Antonio said. The clock is ticking, which creates increasing pressure. This pressure, combined with other constraints related to governance, can lead to a loss of independence. "If founders lose their independence, they may not achieve their vision."

To avoid this situation, some entrepreneurs deliberately choose a different path to regain control of their time and ownership. "It's not so much about avoiding dilution; true entrepreneurs are not interested in getting rich. It's about staying independent and changing the world at a realistic pace," Antonio said.

The siren songs of VCs do not seduce these entrepreneurs easily. "They have a different mindset: They think in economic terms, not financial terms," Antonio said. They develop their company so that it can create value without the financial obligation to increase its capital. "In the end, all that matters is the customer and the ability to generate revenue organically. It allows entrepreneurs to be financially independent and not be forced to accept money from VCs," Antonio said. That is his definition of bootstrapping.

Bootstrapping redefined

Bootstrapping is not about growing businesses without raising any capital or without any VC support. Bootstrapping is about creating an environment that gives founders a choice to raise capital or not, and when they do, they have more options to select the partner, the timing, and the terms. This is strategic.

For example, Gmelius, a collaboration platform for Gmail, is a bootstrapped company. They started without a VC. Then, Florian Bersier, CEO and founder, decided to accelerate its growth with Y Combinator and a VC in the US (Fyrfly). This was not a financial decision but a strategic one. They chose their time and their VC with a purpose: to grow the US market. That's bootstrapping.

Proton Technologies, the developer of ProtonMail, the secure communications platform, is another case. They initially chose to partner with a Tier 1 US company VC (CRV), but they had to dissolve that partnership due to the particular nature of their business (see blog post here). In the early years, Andy Yen, CEO and co-founder, restructured the product portfolio to pursue a strategy without VC. Now, they have many options—including the option to partner with a VC. This is bootstrapping, too.

Bootstrapping works exceptionally well for tech-entrepreneurs in one of these contexts:

The company is a pioneer and has the first-mover advantage. That's the case with Proton Technologies, which pioneered Internet privacy. There are many examples of this in the US: Dell, Apple, Microsoft, GitHub, Mailchimp, and Craigslist. Their founders have had time to build a lasting business without massive venture capital. Even Facebook somehow bootstrapped because Mark Zuckerberg always kept control of its business.

The company sells enterprise software that does not depend on an extensive community but the needs of businesses. Alohi, which offers advanced online fax solutions and legally binding electronic signatures, fits into that category. It is similar for SaaS with a B2B audience. They need a few happy customers to start generating revenues and develop further organically.

The company positions itself in a niche with the option to sell high-priced services. Cleverdist, founded by industrial IoT experts from CERN, made a name for itself in system control and monitoring. This strategy has enabled the company to grow and break even without external funding. Their current challenge is to transition from services to products.

The company is a university spin-off where much of the research and development was supported by the university. Plair, a hard-tech company that monitors real-time microbial levels in the air, worked with the University of Geneva to develop their prototype and then arranged the technology transfer. Much of the initial technical R&D was developed—and therefore funded—within the university.

All these FONGIT companies have benefited from some of Switzerland's specific advantages for businesses: a first-class data protection law (for ProtonMail, Gmelius, and Alohi), partnerships with universities (for Plair), and CERN top-notch expertise (for Cleverdist).

Hence my question: "Is FONGIT the showcase for a Swiss Valley model?"

Toward a Swiss Valley model

"I see an opportunity for Switzerland and Europe to integrate the best of the Silicon Valley model into a more conscious and sustainable way of growing and funding companies. In Switzerland, we have the proper infrastructure and support system to do this," Antonio said.

"We are also exactly on the path that Jeffrey Funk suggests, which is to focus on creating breakthrough technologies, not just improvements. Innosuisse, the Swiss innovation agency, plays a key role in developing these technologies with a unique approach: it puts science at the heart of the innovation strategy with massive funding for universities and schools that help entrepreneurs," Antonio explained.

Another pillar is the role that both Switzerland and Europe can have in a context of economic polarization—between the US and China. "We should continue developing, protecting, and leveraging the critical infrastructures necessary to develop technology/industry leaders in the most strategic areas such as cybersecurity. This is a matter of sovereignty," Antonio said.

Combined, all the above arguments pave the way for a solid and efficient Swiss Valley model that can influence entrepreneurs and benefit societies worldwide.